“Mathematics is present in dance, in painting, in our body, and a thousand other things.”

Mathematics is not to the general liking of many students. One of the main reasons is that we cannot ground the concepts learned in our daily lives or believe that we cannot apply everything we learn in an actual situation. But, who doesn’t like music? Did you know that math and music correlate perfectly? Tango, for example, is a discipline that I have been practicing for ten years. It is highly demanding. Its high level of complexity attracts those who practice tango compared to other dances.

In a tango dance, in addition to appreciating the physical contact of the dancers, the body movements, and evident energy consumption, we note something more profound is required: a great capacity for concentration and memorization to perform continuous mathematical exercises. That’s right; mathematics is latent during the tango.

“Some tango poses follow symmetry relationships forming parallel lines between the legs of the dancers, and in some tango steps polygons are formed.”

In mathematics, as in tango, we observe different structured forms, which allows us to make a mathematical reading of the dance by identifying the elements that appear. Join me to analyze a piece of tango and identify its mathematics.

How are tango and mathematics related?

Let’s imagine that we are in a “milonga” (a place where the tango is danced socially). A tango begins. We are standing on the dancefloor about to assume an embrace, ready to start dancing. The music sounds, and we identify a rhythm (numerical pattern). We start moving to the 2 x 4 beat, the tango rhythm. We dance the floor in a counterclockwise circle (this is a characteristic of the milonga). We are connected, and the man (or the guide) proposes through his body a series of movements that the woman (or the other person) will follow, like a mathematical function where the input value delivers the output value.

In many poses characteristic of the tango, symmetrical relationships are established. The legs of the dancers form parallel lines; some dance steps even form polygons.

Image 4: Parallel lines. Photographs: Lorena Garram (2015).

Image 5: Parallel lines. Own image.

For example, when the woman positions herself as the central axis, and the man rotates around her, making a circumference, creating a “merry-go-round,” these symmetrical relationships generate a sense of harmony and order.

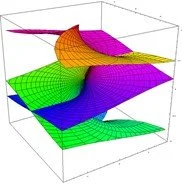

When a set of movements occurs in which the movements of the couple’s bodies are inscribed in an invariant plane (for example, a shared spin around the same axis and its associated operation of composition), we can conceive it as forming a group in abstract algebra.

Image 6: Dancer spinning around her axis

A group is an algebraic structure formed by a non-empty set endowed with an internal operation that combines any pair of elements to compose a third inside the same set, satisfying the associative properties; the neutral and symmetrical elements exist.

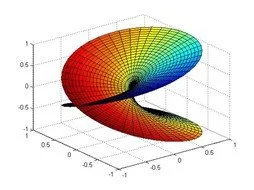

If we study the advance of the couple’s positions through time, considering the dynamic system’s movements, we can describe it with differential equations. Sofia Kovalevskaya was a Russian mathematician who studied this type of equation, where a solid is modeled that rotates around a symmetrical axis. We can think of the dancer’s body spinning around its central axis.

We can think of music like the German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who stated that “music is the pleasure that the human mind experiences in counting without realizing that it is counting.” We relate rhythm as an intuitive branch of elementary mathematics called arithmetic: think of a bounce, cut step, or misstep.

Projecting this to the tango floor, we can understand the space as a Euclidean vector space, where through our movements, we form straight lines, and we displace them through translations and turns (thinking of a more traditional tango). When we talk about curved movements and body positions with more contortion, we speak about the varieties of Euclidean space (particularly the curved space). Varieties can be treated locally like the Euclidean space whose curvature is null, but, overall, they have other properties far from it. Spaces with continuous curvature are called Riemann varieties; some examples are elliptical space, hyperbolic space, or any curved surface of R3.

To know more about the Riemann Surface, consult here.

In a choreography, we find an ordered numerical series with the musical times inverted in the steps, a mathematical succession that repeats throughout the composition. It leads us to think about mathematical recursion (a problem that can be defined according to its size, be it N, divided into smaller pieces of the same problem (< N), and the definitive solution to the simple pieces becomes known). Some people have also composed music with fractals.

Reflection

Sometimes, it isn’t easy to think of art and exact sciences acting together. However, mathematics is present in dance, painting, nature, our bodies, and a thousand other things. This article described only some of the relationships between tango and mathematics. Still, I am sure that even more commonalities inspire us to appreciate both disciplines with greater precision and passion. I invite you to look for the applications of mathematics in some dance of your liking. It is just one way that mathematics shows us how wonderful, powerful, and indispensable it is for us in the world.

The title of this article refers to a successful Mexican quintet called “Entretango” (in English, “Between tango”). I thought this title would be attractive to the knowledgeable public because of the hidden message. I invite you to share more ideas on how mathematics relates to our daily activities through an article like this in the Observatory of the Institute for the Future of Education of Tecnologico de Monterrey.

About the author

Nereyda Analy Villarreal Lozano (nereyda_avl@tec.mx) is a chair professor in the Department of Mathematics at the Prepa Tec Eugenio Garza Sada campus. She is 30 years old, a teacher for ten years, teaching 6.5 years at Prepa Tec for ten years. She also teaches mathematics workshops for students new to high school and entering professional baccalaureate programs. Previously, she published in Edu bits the article entitled “Can We Learn Mathematics Using Only a Jumprope?” Of course, she has been dancing the tango for ten years.

Edited by Rubí Román (rubi.roman@tec.mx) – Observatory of Educational Innovation.

Translation by Daniel Wetta.

This article from Observatory of the Institute for the Future of Education may be shared under the terms of the license CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

)

)

)